Lamb of God returns from Pet Sematary as zombie content

This email is powered by the trouble between metalworkers, AI, scratched CDs and the cloud. Doing strategic design, I’m always navigating tensions around narratives of change, often ostensibly involving “technology” or some desired or feared “disruption”. What do such narratives mean? Is change always good? Is there anything interesting in the detritus left behind? I’m always drawn to ambivalence.

So it’s no surprise that in the wake of Easter, my thoughts hover above the border between death and rebirth, collapse and resurgence, obsolescence and renewal. And as Passover season led into May Day, I was reminded that in order to find new life, we sometimes need to do more than just hustle like good neoliberal subjects, and actually mess up the one around us, like the plagues visited upon Egypt, or industrial action.

I keep thinking of that awesome first-season finale of American Gods: wily old Odin tells Ostara, the ancient pagan goddess of Easter, that she’s sustained only by the meagre echo of Spring festivities that survive in our contemporary chocolate egg rituals. It’s time to demonstrate her true power to the New Gods, he says. So in the devastating penultimate scene, Ostara decides to withdraw Spring from the world, leaving the land withered and gnarled.

Easter (the ever-delightful Kristin Chenoweth) withdraws her labour.

Says Odin:

Tell the believers and the non-believers. Tell them we’ve taken the Spring. They can have it back when they pray for it.

Such chutzpah: it’s the Earth, going on fucking strike against the World. So if a Norse god union organiser calls on you next Passover/Easter/May, on which monstrous powers will you draw? How will you Show Them Who You Really Are?

Happy May.

STATION IDENT: After returning to design after a year away, I find that Everything Now Looks Very Strange Indeed™. This is another one of my updates on restarting a creative practice, with added cultural and design commentary.

(If someone’s forwarded this thing to you in the hope you’ll find it interesting, you can subscribe here to secure my everlasting love. And please, pass it on if you think it might be of interest to anyone.)

🔂🌏 The eternal return of post-human-centred design

Giles Lane from Proboscis took some time to wrestle with my recent ambivalence about human-centred design. Recapping: back in Issue #2 I asked, “Isn’t putting humans at the centre of things what got us into this climate disaster?”, to which Giles replied:

I have a very different understanding of Human Centred Design based on needs rather than desires, including the need to co-exist within a healthy environment/ecosystem. It draws on its 1970s roots, based in radical response to exploitation of people & communities by privileged elites.

Those of us whose work has always embraced a dialogue about ethics, values and been infused by a genuine concern for human centred, participatory design will always be on the periphery of the mainstream.

The thing is, Giles and I don’t have a very different understanding of human-centred design — I completely understand where he’s coming from. When onboarding new designers at Digital Eskimo, I was always at pains to emphasise how the heritage we were inspired by — the Scandinavian participatory design tradition, amongst others — was a truly radical seam of practice that had been papered over by the rather less exciting idea that “listening to customers is common sense for business.” 🤮

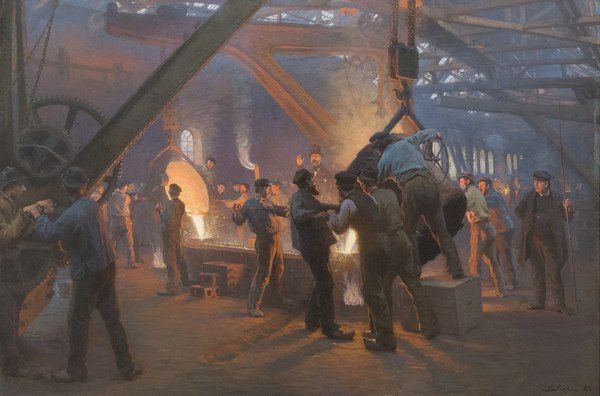

"From Fra Burmeister og Wain's Iron Foundry" by Peder Severin Krøyer, 1885.

I would argue that contemporary design methods, whether they acknowledge it or not, owe a massive debt to organisations like the Norwegian Union of Iron and Metalworkers, who in the 1970s were disruptively intervening in debates about automation and computerisation. Rather than simply being “for” or “against” the machines that were threatening to replace them, workers became high-level designers of workplace technology systems. Now that debates about automation have again recurred in this age of AI, we would do well to pay attention to these traditions.

But I’d still argue that in spite of the traditions Giles and I both still cherish, the balloon of “human-centredness” has nonetheless semantically burst, and was never completely tenable in the first place. An analogy: “Third World nationalism” presided over some heroic moments in the struggle against colonial domination, but I nonetheless think that nationalism was never exactly a good thing in the first place, and also tends to yield ever-decreasing returns as a corrective to very real global inequalities.

I think we simply need new beacons for navigating our more-than-human design landscape. These landmarks might include the work of people like Anab Jain from Superflux (see this talk at the IxDA’s Interactions 18 for a good overview of her work), Anne Galloway from the More-Than-Human Lab and others. Let’s all watch that space, and please let me know if you find anything interesting — I’ll feature it here in a future issue.

🐕🤖 Old dogs, new

I was at the City of Sydney’s latest CityTalk, “Our Future With AI and Its Rise In China”: a keynote from Robert Hsiung, chief of the online tech education platform Udacity in China. I found the evening singularly unimpressive. Rather than indulge in wide-eyed liberal panic about Chinese authoritarianism by mining a seam of yellow peril rhetoric, the subsequent conversation went in the other direction entirely, studiously avoiding any discussion about machine learning’s use by the Chinese surveillance state.

Hsiung emphasised the importance of “mastering the machine” to staying relevant as humans in an AI world, citing case studies in which “even” blue collar Chinese workers with a mere secondary education were successfully retrained by Udacity as AI programmers. Sure, they want to democratise tech skills, and I agree that adaption is preferable to sticking one’s head in the sand, but when Hsiung characterises people on society’s periphery as “people who didn’t study enough in school” (actual words used), I’m not seeing Norwegian metalworkers taking power into their own hands. I can’t help but wonder there’s an implicit element of patronising, tut-tutting disciplinary action in this imperative to retrain before the Singularity overwhelms the uninitiated.

Hsiung’s keynote ultimately devolved into a stiff, extended advertisement for Udacity, reminding me of nothing so much as a dystopian propaganda spot for a corporation like Omni Consumer Products in Paul Verhoeven’s RoboCop. If this deeply uninteresting event is the best the city’s public sphere can do on the AI front, Lord Mayor Clover Moore ought to be embarrassed.

💿☠️ Obsoletely nothing

I’m alive / I’m dead

— The Cure, “Killing an Arab”

Image by Rishi Deep at Unsplash

When I realised not long ago that some of my primary school art students were habitually getting stuck in their creative endeavours, I got them to look for stimulus in unlikely places. “Look at what’s been thrown away at your feet,” I told the class. The next day, my own advice returned to me as a gift.

Local government rubbish cleanups are the rhythmic heavings of the suburbs. A few times a year, we find the unwanted and the outmoded disgorged onto the street (and more often than not, you can find me rummaging through the junk). As I got off the bus that afternoon, an object on the pavement suddenly came into focus as having joined the the ranks of the obsolete: a CD tower. A tall, narrow shelf, made solely to hold a large collection of compact discs.

A few years before, it had been cathode ray tube TVs and VHS tapes on the nature strip. Today, a piece of furniture had lost its one purpose. Next to it, victims of the streaming moment, were endless shiny platters: redundant CDs and DVDs. I felt a pang of melancholy at this diorama of churn, but couldn’t muster up any actual nostalgia for CDs. I suspect that I’m not alone in this.

In 1998 I wrote a short science fiction story that touched on the possibility of being nostalgic for media formats that were then only just beginning to be challenged by new forms of media like the Internet. Mirroring what I was then seeing with the fetishisation of vinyl records, my 21st Century protagonist, Sebastian Tan, was a CD fetishist. While I gave Seb the ability to hack into streaming media services to get lasting access to the discrete music files themselves, this streaming pirate still preferred physical media.

And the act of opening the digipak and sliding the antique CD in place was a ritual. Trainspotting. When he first found Silver Rocket, it was a revelation. It was a place. He’d just stood there, soaking it in – the lost garage punk compilations, the late ’90s Skint family, the Anokha artists. All the music physically in the same room. Old silver platters and everything.

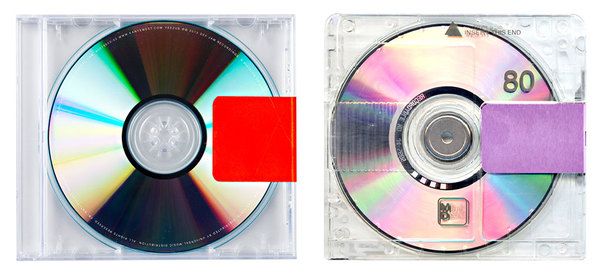

Since this was 20 years ago, I don’t remember how much I actually believed how likely “CD fetishism” would actually be in the 21st Century, but the idea certainly seems ridiculous to me now. Naked optical discs like the CD and the DVD seem to be missing the qualities that would guarantee their fetishisation. There’s something fragile, bare and unromantic about them. It strikes me that this is perfectly illustrated by two Kanye West album covers:

On the left is his 2013 masterpiece Yeezus, which unfortunately affects the style of a blank CD. To the right is its recent sequel, the not-so-great Yahndi, which makes up for its mediocrity by aping a magnificent Sony MiniDisc, a fabulous storage format that was largely outmoded by the turn of the millennium.

Don’t be fooled by the similarities, because these two things are chalk and cheese. MiniDiscs were cool. CDs are not. In addition to enclosing a rewritable magneto-optical disc inside a permanent case, giving them a more tactile quality, MiniDiscs were also smaller in the hand. And in the cinema of the mid- to late-’90s, they were a shorthand for “vaguely futuristic storage media”.

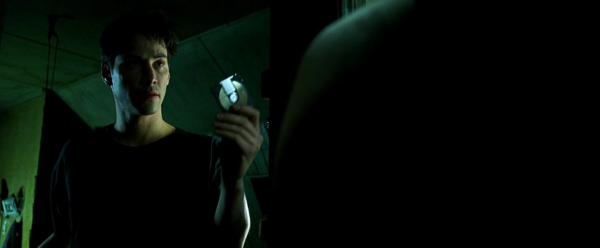

MiniDiscs played a significant role as storage for VR contraband in Kathryn Bigelow’s Strange Days (1995). Ralph Fiennes furtively stashes old VR recordings of happier times with Juliette Lewis in a shoebox of MiniDiscs, but one particular disc that comes into his possession becomes the MacGuffin in the film’s thriller plot.

Gotcha: VR proof of racist police brutality… captured on disc! (See how actually compact it is in the hand?) And in the Wachowski’s The Matrix (1999), MiniDiscs return as contraband, this time stashed heavy-handedly inside Neo’s copy of Jean Baudrillard’s Simulation and Simulacra. By this time they’d become almost retro-futuristic, somehow at home with the acoustic coupler modems and Bakelite handsets.

There’s something reassuringly tangible about the MiniDiscs in these movies. Their secret hiding places are enticing. And the sight of these contraband objects being exchanged for physical cash is just too delicious.

In short, I wish I could be nostalgic for CDs like I am for MiniDiscs (which, truth be told, I never used that much). It’s as if MiniDiscs occupy in my imagination a subjunctive road-not-taken that would have made disposable optical media less crass. I almost feel like mad old King Denethor in Lord of the Rings, wishing that it was his less favourite son who died in battle.

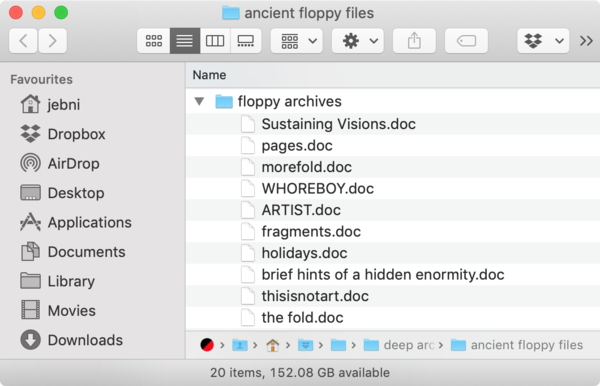

🧟♀️💾 Zombie content

There are folders on my laptop that owe their structure purely to having originated on random old floppy disks that I found in the cupboard. Some of these files are unreadable, despite being Microsoft Word documents. Microsoft are amongst the most slavish followers of backwards-compatibility in the technology industry, even to the extent that they replicate the behaviour of ancient bugs in newer versions of Windows in order for apps to run smoother, but it seems that documents created in versions that predate Word 98 are lost to me. (I’ve learned my lesson: these days, everything’s in plain text Markdown.)

I’m intrigued by the file titled “WHOREBOY.doc”. From what I recall, it contained notes for a graphic novel I was planning about an undead sex-worker-of-colour in the antebellum South. A black 19th Century superhero, Whoreboy kicked arse. At least, that’s what I remember.

Update: turns out that plain text editors can glean most of the content from old binary Word files. My memory proved largely correct. Whoreboy was a runaway slave rent-boy who could sprout tentacles from his back and rise from the dead. In moments of crisis, the old slaver’s brand on his shoulder would glow, perversely triggering latent superpowers. (I’d flagged the branding of African American slaves for further research. These days I’d be in Wikipedia rabbit-hole instead.)

A snippet:

Whoreboy’s mentor, an old “witchdoctor”, mentions Jimbo in the Mirror, the terrifying folk spirit that you can only see at midnight.

“Really?” asks Whoreboy.

“No, I made it up,” he says. “Them white folk love that shit. Brown Eye for the White Guy, I call it.”

Okay, perhaps it needs more work. But think of the possibilities!

What’s the funniest skeleton in your digital closet?

🎼🔁 Refrain, with key change

It’s apparent that I often think inordinately about the past while navigating change, even if it involves a kind of “meta-nostalgia” (as above: when nostalgia doesn’t seem possible, I feel “nostalgic” about “feeling nostalgic”). As I’ve said earlier,

I often look to the past when I think about the very idea of the future, not just so we can avoid repeating “the mistakes of history” (as important as that might be), but because as designers trying to make the world a better place, we really should honour the creative friction that happens when the weird fragments of the past we continue to live with rub against the potentials of the present moment. (For a future-oriented person, I do an amusing amount of hoarding! In my view, forgetting to deal with legacy systems, even if “dealing with them” involves actively destroying them, is tantamount to vapourware dreaming.)

But I’m also realising that to hover in the futurepast in the way I do means more than just coming to grips with the past, with all its traumas and potentials. I suspect that my own retrofuturistic tendencies are an instinctive way to express the bind we find ourselves in as makers of newness (designers, strategists, “change-makers”) under late capitalism: so much of our work these days seems to involve making organisations more adaptable, resilient, nimble and innovative, but how this might also be a friendly form of neoliberal shock therapy? How much is the agility of the contemporary design-led organisation a way to produce subjects who compliantly flex with the ever-shifting sands of the market?

I love to tell people about my work facilitating cultures of design possibility in organisations. After a productive co-design session, a client team-member will express joy about the concepts they’re helping to flesh out.

“You realise, don’t you,” I say, “that you’ve nominated yourself as a key part of the leadership for this project, right?”

The resulting look of terror on their face — the one that says, “B-BUT THAT’S NOT IN MY 12-MONTH WORK PLAN!” — is one that I always relished. And so I drag them kicking and screaming into the future. While I’m not about to defend calcified organisational cultures of bureaucratic planning, I’m now a bit more equivocal; I can see some continuity between my own gleefulness and the forces that are casualising workforces around the planet.

Perhaps my hovering, with my face turned to the past as I explore futurity (and like Lot’s wife as she looks back at Sodom even as she flees), is an admission that security and belonging are worth something in these times. So as we experience the churn of obsolescence and innovation, let’s keep our wits, sympathies and sense of revolt about us.

A sustainable portion of all my love,

Ben