We live in the vortex with all the joy and pain of the universe

There’s a climate to these times.

Last month, as my companion and I walked home after dinner, a ten-year old boy in the back seat of his parents’ car yelled “HEY, CHING CHONG!” out the window as they drove past.

A couple of weeks later, a crazed white woman accosted me as I walked my son home from school.

“You’ve got the plague! Fuck off!” she shouted.

I first got involved in anti-racist activism 30 years ago, and even now I rarely know what to say in such moments. I live in a suburb with one of the most visible Asian populations in Sydney, where you’d think we “owned” the streets. And yet I still have to listen to the nice old white ladies muttering loudly to each other on the bus about how my kind have ruined their neighbourhood. Right in front of me. That sense of impunity never fails to stagger me.

It’s a small bit of turbulence, but part of a much larger storm. The same white supremacist momentum that feeds the brazenness of those poor racist grannies also enables more monstrous, unspeakable and otherwise incomparable things.

You don’t need a weatherman.

Atlanta.

This newsletter, now called Impossible Thing, traces the unexpected connections and paradoxes I encounter in the worlds of creativity, design, social change and cultural politics, as I rethink what it means to maintain a critical and creative practice in forbidding times. I’m finding the journey both thorny and full of wonder.

I’m grateful that you’re following along. Terms like “design” and “politics” usually imply a very instrumental reshaping of the world, but I’m taking a more wayward and elliptical approach, skirting the edges of what it is to be intentional, which isn’t an easy sell. So I’d love it if you forwarded this to one other person you think might vibrate on the same frequency. And if someone’s done this very thing to you, I’d be honoured if you subscribed here.

The eddies of spacetime

During these seasons of cruelty, it’s easy to feel like we’re being crushed in a singularity by a million gravities, because yes, things are epically shit. But facing our own despair also brings us closer to other things. I’ve never understood that old Wobbly slogan, “Don’t mourn, organise!” — as if the two were mutually exclusive. In fact, acts of radical mourning remind me of what matters: during these superdense moments when the horror is at its thickest, the universe’s beauty is sucked into the vortex, too. Not just because we see astonishing acts of solidarity and defiance and care happen in response, though these things are definitely part of it, but also because in a much more basic way, we become attuned to the universe’s existential fabric — the conditions of possibility that also allow for new things to emerge.

I think I glimpsed this within my own despair when Philando Castile was shot in 2016:

In these times of anguish I want to tell my daughter to look up at the sky to see herself in the stars. Because the beauty of the cosmos is all matter and force, and its wonders are testament to the fact that “how things are” in our little lives fucking matters. The fact that a man's chest bursts open and his heart stops beating because another has decided he is prey — that matters. Like everything else that happens.

It’s an aspect of simply existing that we fall through the universe, thrown into the world, blinking and unsteady, and it’s in the most vertiginous moments that we’re reminded of our mass, inertia, and perhaps the potential for other kinds of momentum.

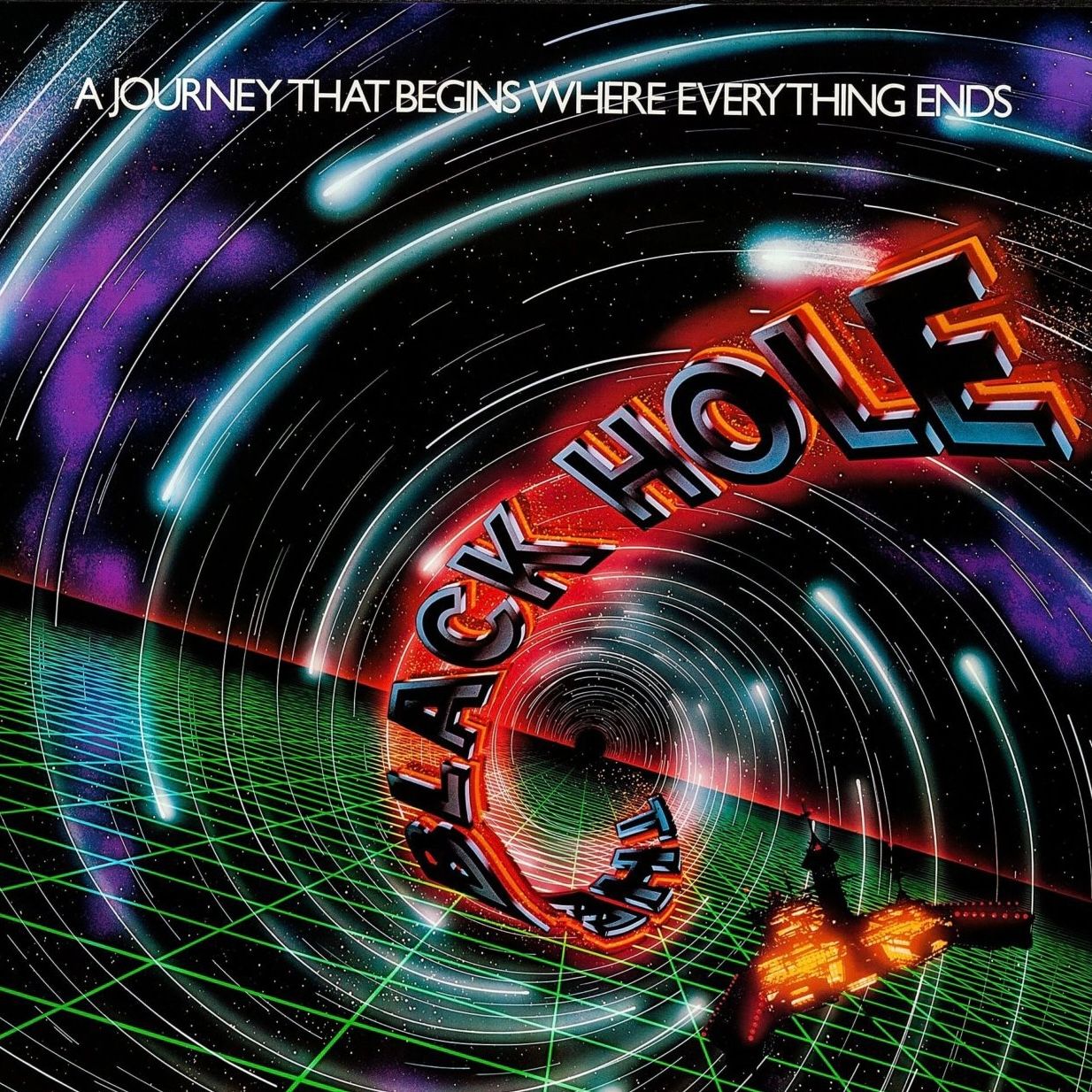

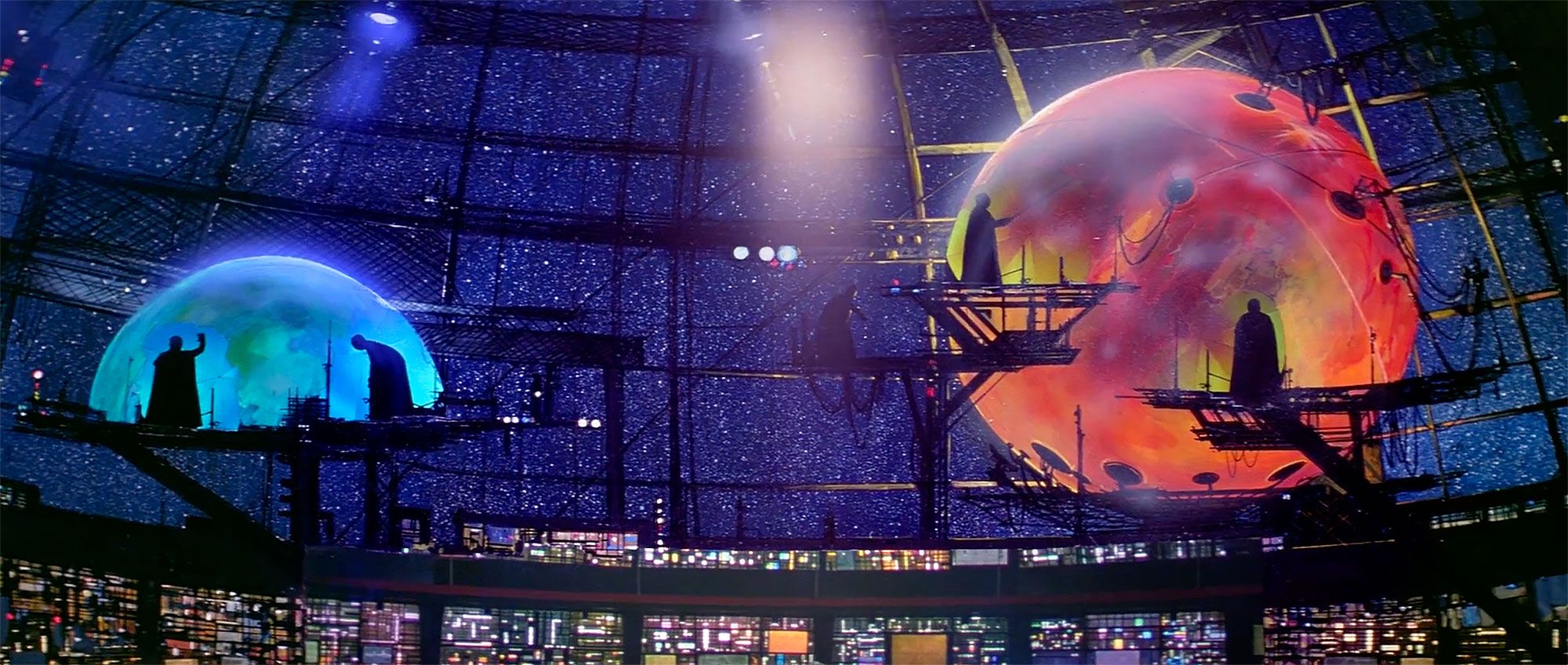

The other day I rewatched Disney’s The Black Hole (1979) for the first time in 40 years. Beneath the veneer of late-’70s space opera cash-in, it’s really more in the lineage of Forbidden Planet — a haunting mood piece, where human obsession meets cosmic forces: at the edge of a black hole, our heroes from the USS Palomino encounter the Cygnus, a huge gothic castle of a spaceship that’s been floating there for 20 years, tended by a mute “robot” crew and a lone mad scientist, Dr Rheinhardt.

My vivid childhood memories of the film proved fertile — those resonant moments were as pivotal as I’d recalled. For example, the true nature of the Cygnus crew is suggested when we witness the drones conducting a silent funeral for one of their own. And as a kid, I’d always found it curious that Rheinhardt’s sinister robot enforcer was named Maximilian, as Rheinhardt himself was played by the scenery-chewing Maximilian Schell. But now, seeing Maximilian Schell snarl “Maximilian!” (to set the beast upon enemies, or call him to heel) is just too delicious: echoing the monster in Forbidden Planet, the robot is clearly a manifestation of Rheinhardt’s Id, and the congruence of their names, by chance or design, is icing on the cake.

Along with the Nostromo in Alien, 1979 was a great year for spaceship names, but why Cygnus and Palomino, exactly? The ancient Greeks knew the story of Phaethon, the son of the sun god Helios, who fatally plunged into the waters after losing control of the luminous horses who drew his father’s sun-chariot across the sky. Of course, a golden horse is a palomino. Meanwhile, Phaethon’s grieving lover Cygnus, king of Liguria and fabled songsmith, refused to leave, camping indefinitely at the water’s edge, and diving in each day to retrieve his boyfriend’s bones. The gods took pity on him and turned him into a swan, but he never left, circling the waters, avoiding the cursed sun, and continuing his mournful swan song.

We, too, mourn at the black hole.

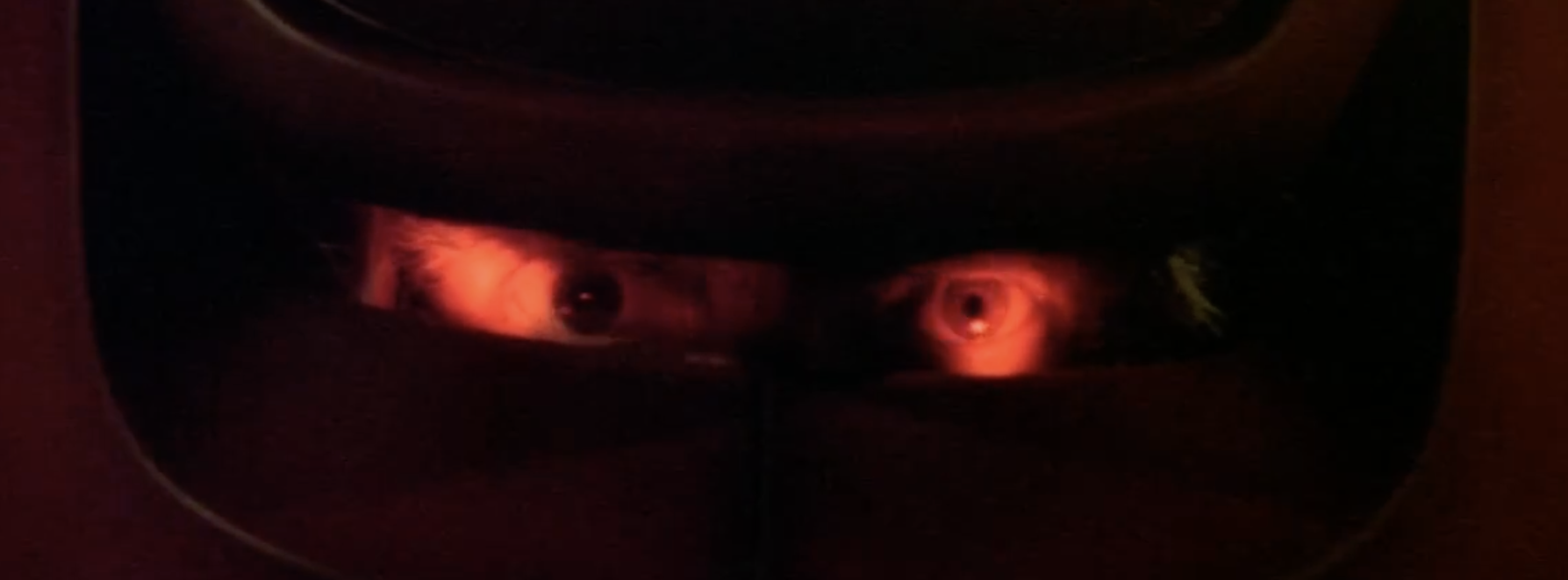

At the film’s climax, it becomes obvious that our heroes can’t escape the black hole. As everyone is inevitably sucked into the vortex, I waited for the shot that had been fixed in my memory: Rheinhardt’s eyes peering out from Maximilian’s visor, the man now magically encased in the mechanism of his own resentments. Our heroes then travel through a cheesy celestial gothic archway and somehow emerge elsewhere, fully intact. Wait, what? The ending I remembered, though still cheesy, was way more weird and appropriate. It turns out that I’d remembered the ending of Alan Dean Foster’s novelisation; in the black hole, the crew of the Palomino are transmuted, still conscious, into the substrate of a new universe:

On a beach was a grain of sand. The sand was part of a continent, the continent a component of a world, the world a speck of substance in the sea of infinity. They were part of that world, part of every world, for in passing out the white hole their substance had become dispersed. An atom of Charlie to a nine-world system, a molecule of Kate to a local cluster of stars, a tiny diffuse section of Holland spread thin over a dozen galaxies.

Their thoughts spanned infinity, as did their finely spread substance, and they now had an eternity in which to contemplate the universe they had become.

Xiaojie Tan. Delaina Ashley Yaun. Daoyou Feng. Soon Chung Park. Hyun Jung Grant. Suncha Kim. Yong Ae Yue.

Let new things emerge in a sea of infinity.

Release the Bats

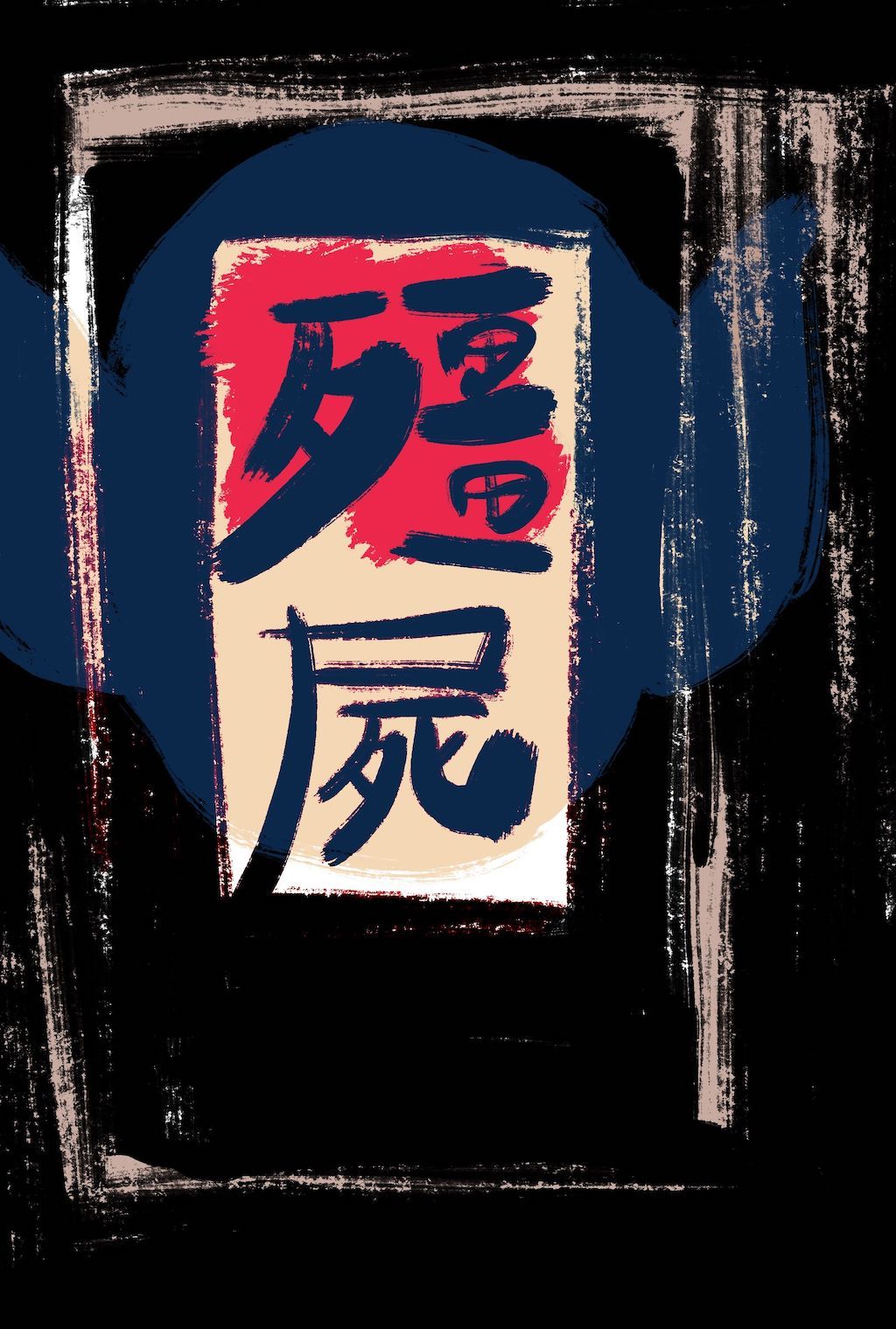

It’s no coincidence that this week I’m working on an art commission as part of the I Am Not a Virus project, which addresses anti-Asian racism, particularly in the COVID age. My piece, Release the Bats, is all about lifting the burden of always having to explain oneself to a racist society:

Rather than plead that “I’m really quite nice if you get to know me,” I’m taking inspiration from one of popular culture’s best known avenging masked heroes: Batman. Unlike more affable superheroes, Batman explicitly uses his iconography to strike fear in his enemies, and in some incarnations to even grapple with his own fear of bats.

Can Asian Australians perversely appropriate the racist associations that attempt to taint us, and reanimate them for our own ends? Through the nightmare figure of the horseshoe bat, with its flat face and squinting eyes, I’m exploring and rerouting the paranoid chain of symbols that can cluster around the cross-species spillover of coronavirus from bat to human in China, making it resonate with the spillover of historically unwelcome Asian immigration into the West.

Can I really reroute that dubious chain of symbols? The next issue will feature more of a peek behind the scenes as I attempt to do just that. In the meantime, please read this tangentially related piece by Robin Sloan on grappling with the racist origins of DC Comics, via his always-fascinating newsletter-blog-thingy.

The Gift of Momentum

As bodies thrown across the universe, we can and must find opportunities to gather our own momentum and access our agency. So to enter my artist proposal for I Am Not a Virus, I had to confront an old skeleton. A couple of years ago I’d submitted an illustrated piece about post-human veneration to an ecologically themed art competition, and it didn’t even make the exhibition:

A Triptych of Icons Restored for Survival Beyond the Anthropocene

(Acrylic, pencil and pastel on reclaimed cardboard boxes)

How can we imagine objects of faith in this era of environmental catastrophe? In this triptych of “restored” Byzantine icons, I explore the unlikely places to which we must look to for our planet to aspire to survival:

(Left) “Holy Mother Mycoderma” — the Virgin Mary as “The Mother”, the abundant bacterial culture that produces vinegar;

(Centre) “He is Risen” — Christ as a Tardigrade, the indestructible microscopic animal that can resurrect itself after years without water;

(Right) “Set My People Free” — Moses as a gigantic sea monster, reminiscent of Lovecraft's Cthulhu, who in this age of climate change can control the waters (and drown the Egyptian army in the Red Sea).

Ashamed, I’d never since shown that piece to anyone, and only posted it on Instagram because I needed to reference it for the new project. For those of us who live in the world of client services, negative reactions from clients are the water in which we swim, but the aura that surrounds Art nonetheless put this rejection in a different gear for me, even though I knew intellectually how bankrupt that precious, romantic narrative was. So I closed myself from any other potential feedback, and even contemplated leaving art behind altogether.

It was heartening, then, to recently get an encouraging email about the piece from Deborah Kelly, an artist whose opinion I respect. Deborah also shared her own rejection stories with me — a fine act of solidarity that is teaching me to grow a thicker art skin — and also asked about the process behind the work, which was probably the best thing about it: the studies I did in my notebook were far more engaging than the finished work, and maybe she could somehow sense this. Seasoned perspectives!

(On stuff that was not rejected: you can catch Deborah’s recent work at the Museum of Contemporary Art, starting this weekend, as part of the The National biennial exhibition of contemporary Australian art.)

More soon.

A sustainable portion of all my love,

Ben