Messages to and from the future: mooncakes vs fortune cookies

As a strategic design consultant I spend a large amount of my time thinking about the future. My work ranges everywhere from anticipating how social services will need to be deployed to an ageing population, to identifying the kinds of supple skills non-profits need to foster right now in order to be future-ready. How are we going to be, as a society?

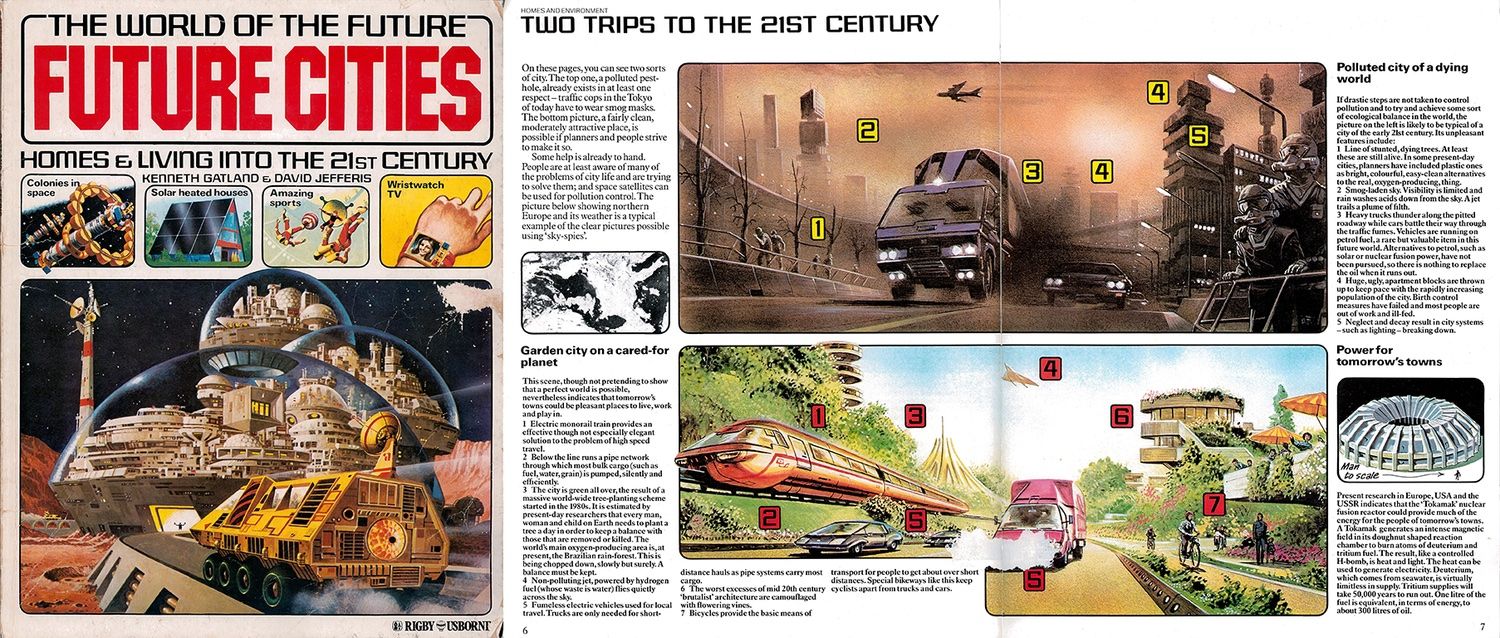

It’s always been this way with me: as a child, my bookshelf was full of wide-eyed educational extrapolations into the distant 21st Century, epic science fiction novels, and tomes about artificial intelligence. Good times!

Indeed, I often look to the past when I think about the very idea of the future, not just so we can avoid repeating “the mistakes of history” (as important as that might be), but because as designers trying to make the world a better place, we really should honour the creative friction that happens when the weird fragments of the past we continue to live with rub against the potentials of the present moment. (For a future-oriented person, I do an amusing amount of hoarding! In my view, forgetting to deal with legacy systems, even if “dealing with them” involves actively destroying them, is tantamount to vapourware dreaming.)

So it’s not any one future as an end that I’m looking forward to, but rather a critical orientation towards futurity that we as a society will need in order to prosper alongside the other things with which we share this planet. You could say that it’s the most crucial line of inquiry of all: as a society, what’s the difference between what’s currently deemed important and what should be important? And how do we help bring the required change into being? Big questions. Political questions. Questions of vision.

What metaphors should we use as guides to navigate such questions? What’s our style of future thinking?

I write this on my birthday, which in 2017 also happens fall on the day of the Chinese Moon Festival. To mark this harvest festival, we Chinese traditionally eat mooncakes: delicious packages of lotus seed paste wrapped in crumbly pastry. And for me, mooncakes are a great way to think about our orientation to futurity, especially if you contrast them to their tackier cousin in the “Chinese food” universe: the fortune cookie. Fortune cookies are those crispy things that contain cheesy aphorisms about your future on a slip of paper. You crack open the cookie, and you read your fortune in a terrible suburban Chinese restaurant.

I’m sorry, but fortune cookies are bullshit. I’d argue that if you want to prepare for the future, a mooncake is much more useful model than a fortune cookie.

Why is this so? Firstly, fortune cookies aren’t even Chinese, and are probably a relatively recent Japanese invention that only got retconned into Chinese cultural history during World War II. But more importantly, they’re kind of evil.

In this week’s episode of the excellent Star Trek Discovery, we were introduced to Captain Lorca, the first captain in the main cast of a Star Trek TV show that you could imagine committing war crimes. In his first scene, the secretive Lorca offers our protagonist a bowl of fortune cookies, telling her that his family was once in the fortune cookie business. Like his ancestors, Captain Lorca is still in the business of the future: the Federation is now waging a war against the Klingon Empire, and he wants to be one step ahead of his enemies, to the point of co-opting dangerous experimental research on interdimensional travel for military purposes. Essentially, he has his own Manhattan Project on the boil.

It’s fitting that Lorca is obsessed with fortune cookies. His orientation to the future is all about sublimating his need for military supremacy into predictive certainty. The research he’s co-opted is fantastically creative, but Lorca has subordinated it to the logic of monarchs and generals: he seeks a shortcut to the future in order to stay one step ahead of the Klingons, and develops it in secret like an elite 23rd Century Bond villain. For Lorca, this is who the future belongs to. Indeed, he says (contrary to the need for ethical standards and in favour of the ends justifying the means) that “context is for kings”.

What, then, of mooncakes? Fortune cookies are actually just a pale contemporary echo of the more powerful story of mooncakes, and the role they apparently played in the the Chinese overthrow of the Yuan Dynasty in the 14th Century.

At that time, China had been occupied by Mongolian forces for a hundred years, and as they planned their revolution, Chinese insurgents used mooncakes as vehicles to collectively coordinate the uprising against their occupiers. Fortune cookies contain bullshit messages that purport to predict the future, whereas 14th Century mooncakes were designed to carry messages that were a collective call to action. Rather than turning to prediction in order to stay on top, the population worked together to create a future in which they were free.

In some accounts, a slip of paper was hidden in each cake, stating the time of the uprising as a kind of open secret amongst the entire Chinese population: “Revolt on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month”. In other versions of the legend, this message was encrypted into the patterns on the top of the cake, and could be decrypted by slicing the cake into quarters and rearranging the pieces. So cool.

But regardless of exactly how the system worked, I find the contrast in disposition between fortune cookies and mooncakes useful in how we can think about the future.

When we think about the thorny problems that organisations and networks of people and other beings are going to face in the coming years, like coping with the now-inevitable consequences of climate change, or finding new systems to ensure food security, will we hanker after the hubris of kings, for whom the future is the secret to an endless reign, or can we instead see the future as an open secret, a common conspiracy of hope, that’s less about making grand predictions and more about coordinating our current creativity as an act of grassroots rebellion?

If you’re part of an organisation that wants to be future-ready, are you going to plot like a Bond villain or king who wants to live forever? Or are you going to work with your communities to co-design a surprising future?

On this birthday, I feel like a mooncake future. 😀

(Unfortunately, the mooncake emoji does not yet exist in the wild, and is scheduled for release in 2018.)

First published on Medium.