With a coffee grinder in his hand

Oh look, I wrote a ranty thing about Facebook’s work culture of compulsory positivity.

After taking an extended break from social design work “to get some perspective,” I find that Everything Now Looks Very Strange Indeed™. This is another one of my updates on restarting a creative practice, with added cultural and design commentary.

(If someone’s forwarded this thing to you in the hope you’ll find it interesting, you can subscribe here to secure my everlasting love.)

Edible encounters

It’s satisfying that so many of the threads I’m following to renew my practice were first spun last year in the classroom (see Issue #1).

I didn’t know it at the time, but I started volunteering at my kids’ school to rediscover and share something from my own childhood: an aspirational sense of wonder. As a kid, my favourite books and TV shows gave me the feeling of being washed up on the shores of a mysterious island that demanded exploration. While so much contemporary content feels narrowly tailored for particular demographics, there was a looseness and breadth to my favourite ’70s and 80s media, like Usborne’s World of the Future, Choose Your Own Adventure™, Martin Gardiner’s Aha!, or even Sesame Street: the jokes that went over my head or the references that seemed slightly too complex for someone my age were like tantalising glimpses of a larger world. I wanted to play with this kind of challenging curiosity.

My daughter’s teacher also helpfully threw me in the deep end when she initially sized me up. “What do you do, hmmm?” she grunted, channelling Aughra from the Dark Crystal. “I’m a designer.” “Hmph. Okay then, you’re teaching art.” This unexpected arrival of art was a blessing.

So art and aspiration it was. In one of my first classes, I had my second-grade students all do a still life drawing. It wasn’t just an exercise in technique, but a moment to grapple with our place in the universe. I asked them to take the contents of their lunchboxes, place them on their desks, and “really get to know them”.

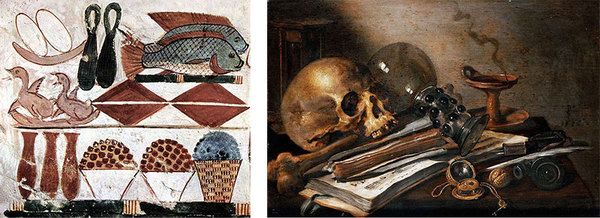

What does it mean to represent an ordinary thing? Throughout history, artists often rendered everyday objects with religious intent. (I’ll return to this.) And since modernity, we’ve had more secular revelations: that the mundane can be dignified or even glorious in its own right; and that conversely, media saturation can make glory and glamour become mundane. Meanwhile, in the here and now, what would the students’ lunches reveal to them? I like setting high expectations.

Lunch was a kaleidoscope. Eight-year-old Nina made six renderings of the same sandwich to “demonstrate different levels of abstraction” (her exact words). Another girl, Anvita, conveyed deliciousness through aspirational magic-realism: her cupcakes were gilded, and were placed in impossibly luxe settings. One vocal faction, unthrilled by the food choices made by their carers, clinically documented their unappetising lunches, reproducing the typography on the packaging of their processed food in detached detail.

All of these scenarios, from the historical ones to the golden cupcakes, are built upon basic encounters that test the edges of our being. In a still life, we meet some objects. Some might be alive or organic, others are not. Some have been fashioned by humans, others not. What can it mean? I don’t think it’s productive to scoff at the ancient Egyptians’ hope that their food would follow them into the afterlife, or use the moral lesson of the fleeting vanity of earthly life as a rejoinder. Instead, the common preoccupation with death in these traditions highlights something beneath the layer of mere belief: we’re grappling with the bonds and the limits of being in a world that extends beyond us. What kind of barrier does death impose on our relationship to (our) things?

Beyond the idea that our possessions are impermanent, the skulls that haunt Dutch Golden Age paintings show us the hubris of our anthropocentrism: death’s grin slices away our philosophical ownership of the world. It will carry on without us. On the other hand, ancient Egyptian funerary art reminds us that the line between us and not-us is also blurry. Perhaps the ancients knew that we and our culinary delights together formed cyborgs, who deserved integrated burial and representation! (Personally, I want to be buried with my Aeropress and Hario Mini Mill. Because together we form a new being, a Voltron of overthinking.)

My question for you, my lovelies: what objects should be buried with you? What’s so vital to your performance of being human that it counts as part of you? It might be a tool or a cultural artefact or a person or an edible thing. Let me know in a reply and I’ll report back any delicious findings.

I wanted to show my students that to draw a still life means becoming a little more sensitive to the gravity of such intimate encounters. And that we shouldn’t be surprised by the trace of activity in the original Norse root for “thing” — “Þing: an assembly, a meeting, a matter for general discussion.” (Hence the name of the world’s oldest parliament, Iceland’s Alþingi or “All Thing”, which originally stood on Þingvellir, the “Thing Fields” or “fields of assembly”.) So when we render the subjects of a still life, we come into an assembly with them. We shouldn’t take such meetings for granted.

It’s a thing

This classroom encounter has inspired my new operation: Studio Thing, which will put art, design and learning in new configurations. There’s plenty I still need to unpack, but for now the priority items from my experience are: (1) the unexpected arrival of art, (2) the significance of basic encounters with the non-human, and (3) encouraging freedom of movement via “looser tailoring”.

The unexpected arrival of art

As someone who gets paid to make things for clients, I’ve furrowed my brow over the work of people like Dunne and Raby and muttered, “but that’s art, not design.” And yet after art unexpectedly appeared on my classroom agenda and became a platform for upending the world, I’m more interested in how “art thinking” might complicate the instrumental logic of design. Design is (almost by definition) a means to an end, but both the “means” and “ends” of that formulation can be mutated by the weirdness that art brings to the table.

The significance of basic encounters with the non-human

I recently spent seven years as a director of a design studio that intervened in problems of sustainability and social purpose with human-centred design methods. It was very special. But just as all those buzzwords were reaching mainstream critical mass, I began to suspect that “human-centredness” was part of the very problem that ecological justice needs to overcome. Isn’t putting humans at the centre of things what got us into this climate disaster? I obviously prefer actually listening to people over my Assumption Autopilot, but over-privileging human voices, especially if they’re playing the classic roles of customer or consumer, creates huge blindspots in our planetary design imagination. So how does post-human-centred design begin? We need the design equivalent of the deep meditation that a still life requires. Things are encounters, and we must make those meetings count. Humbly acknowledging our imbrication in non-human assemblies seems like a step in the right direction for me. I want to explore that.

Encouraging freedom of movement via “looser tailoring”

Our contemporary world demands that thou shalt know thine audience, and thou shalt tailor thine output to suit thine audience. And just as human-centredness can be problematic, our ensnarement in these feedback loops is precisely one of our biggest problems at the moment. It’s not just “algorithms” that have created our social media quagmire, and neither is it just a social media problem. It’s the entire orientation of our cultural economy, and design is heavily implicated. In self-help psychobabble, design’s quest to understand its users isn’t being used to maturely negotiate our relationships. Instead, it’s enabling toxic, people-pleasing codependence and generalised addiction. Our overeagerness to “give people what they want” by tailoring our output to fit very specific user types or audience segments is narrowing our repertoire of thoughts and actions. Uncritical “design empathy” has led to the perfection of capitalist interpellation rather than emancipation.

In the classroom, I got to experience how making things strange and difficult and inappropriate can be wondrous. Rather than going for the perfect fit and encasing our test subjects in carbonite, we need to widen our hailing frequencies to enter the undiscovered country. This doesn’t mean I want to stop investigating and listening in my design practice, but I do want to ensure it’s the kind of curiosity that leads to unexpected places rather than, you know, The Matrix.

Anyway, the whole venture is all still under construction. I will meet you in the Thing Fields.

Edibility redux

After everyone had drawn their lunch, I showed the class one of my own still life drawings.

“What is this?” I asked, paper in hand.

“An apple,” replied Alice, my daughter’s BFF.

“You’re sure it’s an apple?”

“Yep.”

“…Really?”

Exasperated. “YES, BEN. IT’S AN APPLE.”

With that, I crumpled up the drawing, stuffed it in my mouth and ate it. I’ll remember the pandemonium that followed until the day I die.

Until next time, and with another sustainable portion of all my love,

Ben