What Will Come (Has Already Come)

After taking an extended break from social design work “to get some perspective” (ahem), I find that Everything Now Looks Very Strange Indeed.

Hello. You remember me. I design and critique and create tangents. You also probably remember those times you’ve incanted an everyday word, again and again, only to suddenly find that it’s the most alien-sounding thing you’ve ever heard. This newsletter is a series of live updates from that kind of netherzone, drawing from my current process of starting a new creative practice after hitting pause.

(According to my son, this is a Nether Portal. From Minecraft.)

You don’t have to be in the middle of a reboot to feel nether-ish. Do you ever wonder whether the stuff labelled Urgent or Important in your decision matrix bears reevaluation? Is there room to realign your deep relationship with whatever you practice for a living? As critical and creative people (yes we are), what happens when we pry these cracks open and jump in? Some questions by their very nature involve a crisis. Let’s have one together. We all need the chance to ask “Who am I? What the fuck am I doing? Gahh…” without completely losing the plot. I’d love you to join me.

This is also just a place for me to more intimately curate interesting things. Curation as constellation requires a certain stillness. You can’t constellate in a Bullshit Social Media Newsfeed these days. Crisis and stillness. A Recurring Thing. A newsletter about design, change, theory, practice, weird rituals and stuff.

(If someone’s forwarded this thing to you in the hope you’ll find it interesting, you can subscribe here to earn my endless love.)

We all have our seeing machines

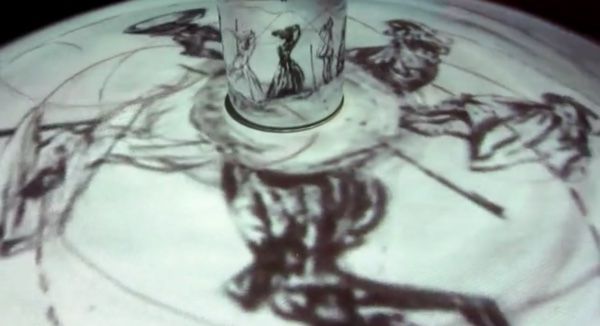

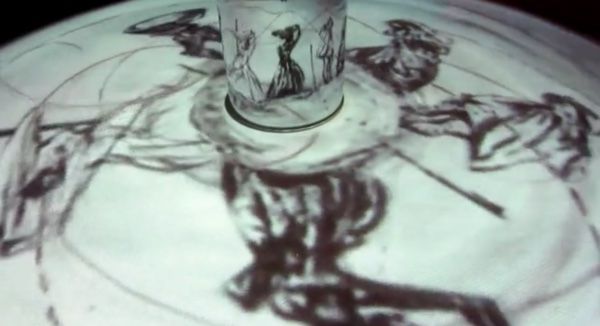

Last week at the Art Gallery of NSW I got to stare, transfixed, at “What Will Come (Has Already Come)”, South African artist William Kentridge’s animated anamorphic artwork about the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935. The film was projected onto a circular table, with each illustrated frame drawn originally in distorted form, to be then brought into recognisable form by a cylindrical mirror in the centre. Check out a video snippet here.

It’s already amazing that Kentridge’s animated work is largely improvised by repeatedly erasing and redrawing charcoal lines on the same pieces of paper. The additional fact that he did all this in 360 degrees through a distorting mirror almost fucking undid me. Ecstatic and nauseous, I instinctively clutched at the edges of the table until a gallery attendant had to intervene.

“What Will Come (Has Already Come)” takes its name from a Ghanaian proverb that resonates with Marx’s quip about history repeating “first as tragedy, then as farce,” and with Battlestar Galactica’s cyclical mythology. This idea of repetition isn’t about defeatist predestination or glib wisdom. It’s painfully interesting. There are always stakes when things recur. Kentridge’s anamorphic setup reminds us that shifting our perspective isn’t simply a matter of finding a more authentic point of view, but that our gaze always has a (technological) structure to it. The curved mirror simultaneously allows us to see and also underscores how contingent that vision is.

My questions for all you lovelies:

- What are the cylindrical mirrors in your life, and do you have stakes in any historical cycles that repeat around them? That is, what are the assemblages that underpin each of our everyday ways of seeing things in our work, in our households and spaces of community?

- How can we cock our heads at an angle, so those relationships become more evident?

I ask not so we can moralise or self-flagellate or simply abolish them, but to first come to grips with our own cultural technologies in a more reflexive way. Do a stocktake, let me know in a reply, and if you give me kind permission, I’ll replay some in a future email.

Given how introverted I am, I’m surprised by the results of my own stocktake: I rely heavily on personal chemistry to make sense of the world. Those of you who’ve noticed my body language when I’m interviewing a superb job candidate with whom I really click can totally attest to this. This isn’t necessarily a problem in itself, but it certainly has its limits and blindspots. It’s not the right apparatus for all situations: if I have zero chemistry with someone, I tend to find them incomprehensible or even forget that they exist, which is certainly something to catch the next time this comes around for me. (More on this below.)

William Kentridge’s self-curated exhibition, That which we do not remember, is at the Art Gallery of NSW until 24 March. I highly recommend it. It is exhausting. And free!

Hot tip: I know nothing about opera, but Kentridge’s production of Alban Berg’s Wozzeckis also coming very soon to the Sydney Festival and looks astounding.

Wonder generator, circuit breaker

The most satisfying and yes, healing thing I did in my Year of Perspective was volunteer in my children’s primary school classes. I predictably couldn’t content myself with being a teacher’s aide, and ended up running regular sessions on design and visual culture for first- and second-graders, covering topics like superheroes in their historical context of sublimated industrial megadeath, Advanced Michael Jackson Studies, typography, speculative futures via design fiction and TARDIS sound effects, etc.

It worked. Parents reported that their children were excitedly reflecting on our topics at home for days on end, but per my own continual amazement at the children’s curiosity and creativity, I think I got the better deal.

Of course, I also found myself grappling with “chemistry being my default setup” in the classroom. When it’s your role to facilitate curiosity and wonder and you succeed beyond your wildest expectations, it’s easy to fall into the trap of simply rewarding your most responsive and articulate participants in an ever-amplifying loop of enthusiasm. Teachers and their pets. It’s similar to the mutual, people-pleasing mire of codependence that can happen between designers and certain stakeholders. (Believe me, I know! Um. Yeah.) Feedback loops can become ends in themselves, and other people and issues can get neglected.

Rather than just feel guilty about this, I had to come to grips with my setup, sharpen my facilitation skills and really emphasise tools to better democratise the classroom — ones that worked at an angle to the kind of charming Socratic dialogue that I still think we need in a classroom (which necessarily differentiates it from something like a co-design workshop). It really felt like victory to deploy tools like Picture Salsa™, Word Salad™ and Thing Dice™, and see the least confident children respond noticeably to a change in tactics. I don’t think it’s reducible to “learning styles”, but it’s probably related to multi-modality. (And given the kind of balance I’ve managed to strike, I’m not sure how to relate my experience to hipster “flipped classroom” models of teaching and learning.)

In any case, teaching kids in a classroom is one the best things I’ve ever done — up there with running blogging workshops with recently arrived refugees, taking ABC staff on psychogeographical walking tours, collaborating with indigenous elders to make a video game, discovering design patterns to better communicate children’s cancer research, etc.

In fact, the joy of teaching has been such a revelation to me that it’s going to be an ongoing and important part of my core practice. More soon.

I hope this has been an interesting constellation of stuff for you. If you subscribe, it will recur :)

A sustainable portion of all my love,

Ben